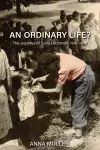

An Ordinary Life?

Anna Müller - Hardback

£42.00

One woman’s national, political, ethnic, social, and personal identities impart an extraordinary perspective on the histories of Europe, Polish Jews, Communism, activism, and survival during the twentieth century.

Tonia Lechtman was a Jew, a loving mother and wife, a Polish patriot, a committed Communist, and a Holocaust survivor. Throughout her life these identities brought her to multiple countries—Poland, Palestine, Spain, France, Germany, Switzerland, and Israel—during some of the most pivotal and cataclysmic decades of the twentieth century. In most of those places, she lived on the margins of society while working to promote Communism and trying to create a safe space for her small children.

Born in Łódź in 1918, Lechtman became fascinated with Communism in her early youth. In 1935, to avoid the consequences of her political activism during an increasingly anti-Semitic and hostile political environment, the family moved to Palestine, where Tonia met her future husband, Sioma. In 1937, the couple traveled to Spain to participate in the Spanish Civil War. After discovering she was pregnant, Lechtman relocated to France while Sioma joined the International Brigades. She spent the Second World War in Europe, traveling with two small children between France, Germany, and Switzerland, at times only miraculously avoiding arrest and being transported east to Nazi camps. After the war, she returned to Poland, where she planned to (re)build Communist Poland. However, soon after her arrival she was imprisoned for six years. In 1971, under pressure from her children, Lechtman emigrated from Poland to Israel, where she died in 1996.

In writing Lechtman’s life story, Anna Müller has consulted a rich collection of primary source material, including archival documentation, private documents and photographs, interviews from different periods of Lechtman’s life, and personal correspondence. Despite this intimacy, Müller also acknowledges key historiographical questions arising from the lacunae of lost materials, the selective preservation of others, and her own interpretive work translating a life into a life story.