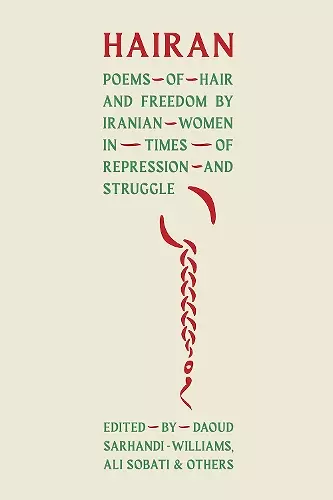

HAIRAN

Poems of Hair and Freedom by Iranian Women in Times of Repression and Struggle

Ali Sobati translator Abbas Shokri editor Daoud Sarhandi-Williams editor Ali Sobati editor Sepideh Jodeyri editor Sepideh Kouti editor Anna Krasnowolska editor Anahita Rezaei editor

Format:Paperback

Publisher:Scotland Street Press

Published:15th Oct '24

Should be back in stock very soon

And do not relinquish the search

For that limitless light

So that in the street, stars

Morph into comets

Extract from 'This Place (...)'

HAIRAN is a new anthology of poetry by Iranian women, compiled in the face of the violent attacks on life and liberty that began with the death of Mahsa Amini in Tehran in September 2022. Amini was arrested and killed in police custody for not covering enough of her hair in public.

Here are 76 poems from a diverse cross-section of contemporary Iranian voices, accompanied by ‘hair portraits’ taken by the poets.

Alongside Sobati and Sarhandi-Williams, HAIRAN was edited by Sepideh Jodeyri, Sepideh Kouti, Anna Krasnowolska, Anahita Rezaei, and Abbas Shokri.

HERE’S the question: When

the majority of the

population of a country

are of a certain opinion,

and their preference forms the rule

of law, should you ever go against it?

And if it is not your own country,

what right do you have to offer an

opinion anyway?

Populism is its own reward: victory

comes with widespread ignorance

because democracy requires education.

Without sufficient education to

know what you’re choosing between,

you don’t really know what you’re

choosing at all. In effect, you have no

choice, just blind faith.

And that’s what increasingly rules

in the world: blind faith in a convicted

criminal, in a “Conservative” Party

whose mere existence endorses class

hierarchy, inherited wealth, a sense

of entitlement, racism, colonialism,

institutionalised theft; or blind faith

in a “Labour” Party whose practices

are not so far removed. Or in an SNP

leadership posing for selfies beside

representatives of English regions

and cities. Is such self-abasement

completely beyond recall?

But there is a deeper question.

Supposing for a moment there are

a few independent minds at work

who see such things happening and

maybe have a chance to point out the

hypocrisies and duplicities, the lying.

Is it arrogance to try to be reasonable

in the face of genocide? Can I present

a calm front while talking about

horrifying violence and the targeted

destruction of non-combatants, men,

women, children, old folk, babies?

Supposing I believe in certain

universal principles. To quote

the Palestinian literary critic and

historian Edward Said, supposing

I believe that “all human beings are

entitled to expect decent standards

of behaviour concerning freedom

and justice from worldly powers

or nations, and that deliberate or

inadvertent violations of these

standards needs to be testified and

fought against courageously”.

To however modest an extent, one is

Abbas Shokri, and how

then, after gathering more

than 200 pages of poems,

contact was made with

Ali Sobati, an Iranian

Farsi-English translator

and contemporary poetry

critic living in Canada, and

the book began to come

together.

The story of the

international editorial

team, comrades in

collaboration with different,

complementary specialisms,

and the beautiful product

itself, published by Scotland

Street Press, is one essential

context in which to read

the poems. See: www.

scotlandstreetpress.com/

product/hairan-poems-of-hair-andfreedom

THERE is a larger context.

More from the Preface: “As

this book goes to press, well

over 200 Iranian protesters

have died, thousands have been

arrested, and unknown numbers

have been tortured.

“Several male demonstrators

have been executed, often after

being convicted on trumped-up

charges under a catch-all crime that

translates into English as ‘corruption

on earth’. Furthermore, many

Iranians have been forced to flee

into exile, joining a diaspora that

now numbers between four and eight

million people.

“Despite ongoing protests,

however, the Iranian regime seems

to be doubling down on its efforts to

restrict women’s rights. Shops will

be penalised if they serve a woman

who enters their premises with her

head uncovered, smart cameras

that can spot women who aren’t

covering their hair ‘correctly’ are

being installed in urban spaces, and

the ‘crime’ of not wearing a hijab

outdoors is being considered for a

mandatory 10-year prison term – up

from a maximum of two months. In

hopefully committed to “advance the

cause of freedom and justice”.

As Said puts it, an intellectual

“is an individual endowed with a

faculty for representing, embodying,

articulating a message, a view, an

attitude, philosophy or opinion to, as

well as for, a public”.

Those statements come from Said’s

1993 Reith Lectures, Representations

of the Intellectual, but that last

description I think might apply

equally well to poets and artists of

all kinds, as well as professional

intellectuals employed in various

capacities, either working for or

publicly criticising corporate bodies,

governments, social states and

conditions. And the poets represented

in a new anthology I’ve just been

reading are all of this kind.

It is one of the most extraordinary

books I’ve seen in recent months.

This is from the Preface, by Daoud

Sarhandi-Williams, co-editor along

with Ali Sobati: “I was sitting at my

desk in September 2022 … when I

heard the shocking news about a

young Kurdish-Iranian woman called

Mahsa Amini. She had been arrested

in Tehran and killed in police custody

for not covering her hair in the

decreed way.

“Throughout Iran, women and girls

of all ages rose in fury against the

regime. The mandatory hijab head

covering, and hair itself, became a

powerful symbol in a struggle for

women’s liberation, personal freedom

and choice. In the autumn of 2022,

I didn’t know much about Iranian

poetry. However, I decided to find out

how contemporary female Iranian

poets were responding to their

oppression.”

The resulting book is both a

compendium of poems in protest

against the killing of Mahsa Amini,

to whom it is dedicated, and also an

introduction to Iranian poetry from

the perspective of writing by women.

The Preface describes how Daoud

contacted the Polish Iranologist Anna

Krasnowolska, who suggested getting

in touch with an Iranian publisher,

Some of the

13 anonymous

portraits

in Hairan

which were

commissioned

for the book.

All were

sent to the

editors in

low-resolution

by messenger

app and

acknowledgements

go to

the unknown

photographers

whose

portraits of

their friends,

family

members

or partners

appear there

The book’s

cover and

(main

picture)

Mahsa Amini,

to whom it is

dedicated

all these ways, public spaces that

are safe for dissenting women in

Iran are shrinking and becoming

more dangerous. The objectives

of this book are twofold: to

share with the general reader

an extraordinary collection of

contemporary Iranian women’s

poetry that has rarely, if ever,

been translated on this scale.

“The verse is passionate,

inspiring, and hallucinatory

in its mix of beauty and horror,

courage and fear, despair and hope.

Collectively, it powerfully expresses

the sentiment words – and poetic

words – can still play a vital role in

bringing about social and political

change. It shows us poetry matters.

“The second objective … is to

promote women’s civil and human

rights in Iran, as well as in other

countries that adhere to similar

or even more extreme doctrines

regarding the role and place of

women and girls.

“As this book goes to press, a

resurgent Taliban in Afghanistan

… has not only banned secondary

and higher education for girls, but

is also bringing back the public

stoning of women judged ‘guilty’ of

some reported moral failing or petty

misconduct. Meanwhile, arresting

and then sexually abusing Afghan

women for ‘bad hijab’ is routine.”

Shouldn’t we in Scotland also be

hoping “that Muslim women will

have the freedom to cover or not

cover their hair, and that both choices

will be treated equally. And that

such basic liberties will extend to all

aspects of their lives”?

That’s the immediate context.

And it should take us back to

the first principles I began with,

Edward Said’s belief that “all human

beings are entitled to expect decent

standards of behaviour concerning

freedom and justice from worldly

powers or nations, and that deliberate

or inadvertent violations of these

standards needs to be testified and

fought against courageously.”

And that, in however modest a way,

and to whatever extent we can, we are

hopefully committed to “advance the

cause of freedom and justice”.

Let me add another voice from a

different continent, at a time when

it’s worth reminding ourselves of the

truly great values and aspirations

America has at times embodied, the

fiercest political poet of that country,

Edward Dorn. He puts it very simply:

“Either we define our allegiances to

certain honorific aspects of human

nature or we don’t.

“Most of us know all the time that

politics in poetry really amounts

to enunciation. Politics in politics

amounts to subterfuge, obscurantism

and hiding all you can.”

So there you are: “certain honorific

aspects” of being human. Nobody,

whatever their cultural history, should

stone women to death or kill them for

showing their hair. Nowhere on Earth

should these things be legitimate.

And that’s the clear enunciation of

every poem in this book, and another

reason why it’s such a remarkable

collection.

And there’s more. The Introduction,

by Ali Sobati with Anahita Rezaei,

Sepideh Jodeyri and Sepideh Kouti,

traces out the whole story of “the

silenced trajectory” in the story

of a feminine voice in “the extramillennial

past of Iranian poetry”.

In the 1990s, Reza Barahani

(1935-2022), a life-long radical (male)

literary critic and theorist, called for

an “alternative womanly narrative”

and suggested that the 1937 novel

The Blind Owl, by the (male)

writer Sadegh Hedayat (1903–51),

as a founding modernist work in

Farsi literature, has been “doubly

problematic” because “in this novel

female characters are denied the right

to bear a name or the right to name –

they are simply not allowed to speak

for themselves”.

The novel presents a surrealist/

expressionist account (drawing on

the early silent movies of Luis Buñuel

and FW Murnau) of characters

“decalcomaniacally copy and

pasted one into another.” But its

attractiveness as surrealist modernism

is undermined by its exclusive

patriarchal priorities. “This situation,

however, is by no means confined

to The Blind Owl … it is ascribable

to almost the entire Iranian literary

tradition and history.”

SO, here’s the drive: “Now it is

time for the woman to become

the narrator of her world and

to do t

ISBN: 9781910895962

Dimensions: unknown

Weight: 370g

232 pages