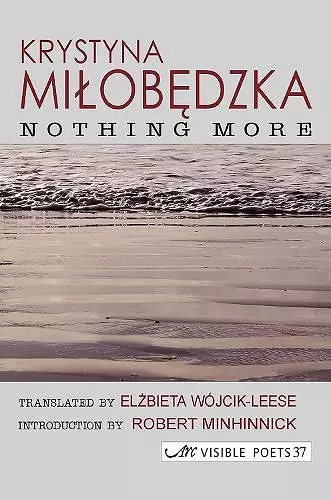

Nothing More

Krystyna Milobedska author Elżbieta Wójcik-Leese translator

Format:Hardback

Publisher:Arc Publications

Published:4th Dec '13

Currently unavailable, our supplier has not provided us a restock date

This hardback is available in another edition too:

- Paperback£10.99(9781906570620)

Milobedzka's poetry crystallizes relationships between people from erotic engagements to the bond between mother and child. These are poems rooted in the earth and body, beginning in a physical experience that expands into philosophical questioning. They are not polite, they do not hide their imperfections. They reveal an immediacy of expression. Each text reveals itself seemingly uncontrolled, an unspecified thought: a sentence broken off, a sudden mental leap, an ellipsis, a slip of the tongue.

In our deep and attentive reading, Milobedzka's understanding of language proves itself so thoroughly thought-out and conditioned by a larger worldview that 'correct' linguistic solutions seem, by comparison with her 'ungrammaticalness,' artificial, inauthentic, incomplete. Her apparently incohesive language amazes us with two features, cultivated with unparalleled discipline. First is elementariness. In this poetry everything is reduced to forms as primary and simple as possible, forms that reach their destination by taking a shortcut, sometimes at the cost of a linguistic error or an oversimplification. When something has no proper name and thus requires a longer elaboration, the poet creates a neologism, even though it may strike us with its inappropriateness among 'normal' vocabulary items. ( - ) Frequently such solutions remind us of the linguistic behaviour of children who, trying to name the elements of the outside world or their own inner experiences, take the shortest route, treading on syntactic and grammatical rules. ( - ) Milobedzka's poetry crystallizes relationships between people into their primary equivalents: the erotic engagement and the bond between mother and child. This reduction is also a complication: the relationships are both most elementary and most complex, they demand utmost responsibility, they ask for the most difficult self-reflection. ( - ) The second characteristic feature is the immediacy of expression. Here each text reveals itself in statu nascendi, seemingly uncontrolled, reporting the birth of the yet unspecified thought: a sentence broken off, a sudden mental leap, an ellipsis, a slip of the tongue. It is no longer a language that is spoken, but a language that is 'being thought.' (Stanislaw Baranczak) 2. Milobedzka desires nothing as much as the world's wholeness. She is possessed by the idea of holism. She seems to be also a pilgrim - in sackcloth - on the path to the entelechy of poetry. She knows that she will never attain it, but she has succeeded in ascertaining that it is not what we seize - but what we are not in a position to seize, what is good and open - that builds us up. Milobedzka's entelechy is also a powerful force more responsible for the condition of the good than for the adequacy of material things. That's how she sees it on her way to the truth. As she goes on, she says that she doesn't expect to discover more. But she should. To gather it all in other words. She is already doing this, already unceasingly saying: to live means to go out of nothingness, always to endure dispersion, to be able at every instant to begin to exist for the first time. I can't break through any further, she spreads her words helplessly. And She-Who-Succeeded-In-Never-Lying even to the smallest part of speech - here for the first time - is lying. (Tymoteusz Karpowicz) 3. What distinguishes Milobedzka's poetry? Let's turn to anatomy for a comparison. Whereas 'rhetorical' poets are interested in human body moved by the will of the brain, and 'introvert-searching' poets are curious about internal organs: the heart and the blood circulation system, Milobedzka peers into the microscopic network of neural synapses, hidden stimuli, invisible links that connect everything with everything. What forces us to stroke a cat, and what makes us wonder in amazement about the similarity between the rustle of a birch and the rustle of blood. Describing Milobedzka as 'cosmic' may, in light of the above comparison, sound absurd. And yet. The microcosmos of her poems transforms without any difficulty into the macrocosmos, when we realize what territories it embraces. If these poems reveal similarity (kinship, the poet herself would say) between the light in the window and the rocking of the cradle, between the shape of the horse and the shape of the apple-tree, between the cage and the woods, that is, between anything and anything, even between a participle and a ribbon in the hair, then we deal not only with a vast imagination which is purely poetic (surrealists, too, knew how to associate everything with everything), but with a certain vision, or rather a spiritual and sensual perception, of the world as a cosmic unity in multitude. Milobedzka seems at times to understand other voices besides our human voice, which she herself uses whenever she speaks and writes. If I'm one with the universe, it's not only me who speaks, but also I am spoken through. I'm both a message sender and a medium through which it is sent. We may suspect that Milobedzka can hear more, that she readily serves as an interpreter between various inhabitants of the same nature. (Tadeusz Nyczek)

ISBN: 9781906570637

Dimensions: unknown

Weight: unknown

128 pages