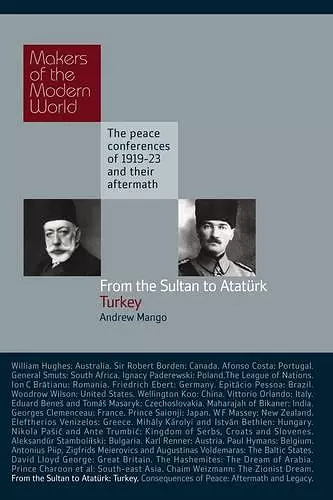

From the Sultan to Atatürk: Turkey

Format:Hardback

Publisher:Haus Publishing

Published:7th Aug '09

Currently unavailable, and unfortunately no date known when it will be back

32 nations fought in the First World War. This 32-book series looks at the seminal events surrounding the Paris peace treaties through the eyes of the key leaders involved - genuinely the Makers of the Modern World.

World War I sounded the death knell of empires. The last Sultan Mehmet VI Vahdettin thought he could salvage the Ottoman state in something like its old form. But Vahdettin and his ministers could not succeed because the victorious Allies had decided on the final partition of the Ottoman state. This book deals with this topic.World War I sounded the death knell of empires. The forces of disintegration affected several empires simultaneously. To that extent they were impersonal. But prudent statesmen could delay the death of empires, rulers such as Emperor Franz Josef II of Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Sultan Abdulhamid II. Adventurous rulers Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany and Enver Pasha in the Ottoman Empire hastened it. Enver's decision to enter the war on the side of Germany destroyed the Ottoman state. It may have been doomed in any case, but he was the agent of its doom. The last Sultan Mehmet VI Vahdettin thought he could salvage the Ottoman state in something like its old form. But Vahdettin and his ministers could not succeed because the victorious Allies had decided on the final partition of the Ottoman state. The chief proponent of partition was Lloyd George, heir to the Turcophobe tradition of British liberals, who fell under the spell of the Greek irredentist politician Venizelos. With these two in the lead, the Allies sought to impose partition on the Sultan's state. When the Sultan sent his emissaries to the Paris peace conference they could not win a reprieve. The Treaty of Sevres which the Sultan's government signed put an end to Ottoman independence. The Treaty of Sevres was not ratified. Turkish nationalists, with military officers in the lead, defied the Allies, who promptly broke ranks, each one trying to win concessions for himself at the expense of the others. Mustafa Kemal emerged as the leader of the military resistance. Diplomacy allowed Mustafa Kemal to isolate his people's enemies: Greek and Armenian irredentists. Having done so, he defeated them by force of arms. In effect, the defeat of the Ottoman empire in the First World War was followed by the Turks' victory in two separate wars: a brief military campaign against the Armenians and a long one against the Greeks. Lausanne where General Ismet succeeded...

'This one stands out for its combination of freshness, conciseness and scholarship.' '...those wishing to inform themselves on the origins of modern Turkey could do no better than to begin with this excellent short book, possibly the author's last, or so he says, but certainly one of his finest.' -- David Barchard Issue 43 2010 From the Sultan to Ataturk: Turkey describes the tortuous rise of the Turkish Republic from the ruins of the Ottoman Empire in the aftermath of the First World War. This book is full of rich details on the ethnic groups, political and economic interests, and migrations within the dying Empire. It also provides a detailed analysis of the key individuals who played a role in the emergence of the modern Turkish Republic. The Ottoman Empire, 'the sick man of Europe', officially died with the Mudros Armistice in October 1918. Under the terms of the armistice the rule of the lands of the Empire was placed in the hands of Britain and its allies. It was envisaged that various Allied-controlled enclaves would replace the defeated Empire and it seemed unlikely that there would be any resistance to this grand scheme. At the time of the Armistice, the former Ottoman colonies in Mesopotamia, Palestine, Syria and other Arab provinces had already been occupied by Allied troops and to this end their eventual separation from the Empire had already been conceived as a matter of fact. What was left of the former lands of the Ottoman Empire was more or less limited to those areas in Anatolia and Eastern Thrace. When the Ottoman Empire collapsed at the end of the First World War, it seemed to many that a regional system controlled by the British Empire would be successfully established. This regional system would comprise an enlarged Greek state extending to Western Anatolia, a Kurdish autonomous region in the east, and the independent states of Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan in the northeast. There had not been anticipated any serious resistance from the Turkish side to this grand design. Within this hopeless situation Mustafa Kemal and his followers utilised every possible opportunity presented by post-war circumstances. Andrew Mango clearly explains how with the help of other like-minded officers and an unlikely combination of local civilian and religious leaders, Mustafa Kemal turned Anatolia into a redoubt of resistance while pragmatically accommodating the decadent rule of the Ottoman sultan for the time being. Both in the military field and diplomatic circles, the Kemalist side followed a multi-dimensional set of policies for success: they used their ethnic and religious prestige among the Muslim populations of the Caucasus and Central Asia to increase their credibility in the eyes of the Bolsheviks. In this way they broke their isolation and acquired a material basis on which to organise military resistance in Asia Minor. On the diplomatic front, they exploited the divergence of policy within the Allied camp and the antagonism between the Soviet Union and Great Britain. In the end, the independence of Turkey was safeguarded as securely as possible between the Soviet controlled lands in the north and the British-influence zone in the south. By 1922, the region in no way resembled what had been predicted five years earlier. The Greek military campaign supported by the British had failed completely, the Greeks were driven into the sea at Izmir, and an independent Turkish state was established firmly in Anatolia and eastern Thrace. Mango describes in great detail how in 1923, a new Turkish state emerged from the ruins of the Ottoman Empire. This was due to a struggle that had extended Turkish involvement in the First World War by four years. Following the departure of the last Greek soldiers from Anatolian soil on 15 September, the ceasefire of 11 October and the evacuation of eastern Thrace by the Greek army, the Lausanne Peace Conference opened on 20 November 1922. While the Lausanne Conference maintained suspense over the conclusion of peace, the year 1923 was a time for the establishment of the basic institutions of the new Turkey. An economic conference was held in Izmir in February-March 1923. During the same months, Mustafa Kemal developed his critique of the economic backwardness of his country and its Islamic culture and the necessity to adopt a new Western identity and to achieve Western standards of political and economic management. The principal goal was to establish a new modern cultural and political economy framework necessary to reduce the economic gap between Turkey and the Western states. This was the period during which the new regime established itself firmly, and started to reform the social and political life in the country. Mango is honest about the 'enlightened despotism' of Mustafa Kemal in this period. The most important issue at this stage was the emergence of the one-party regime and the opposition to it. The creation of a single party possessing the near totality of the assembly seats did not solve the problem of opposition. The opposition began to manifest itself through two major events that took place soon after the proclamation of the republic: the abolition of the Caliphate followed by the expulsion of all members of the former imperial family on 3 March 1924. On 8 April, a National Law Court Organisation Regulation abolished the old Islamic Sharia courts and transferred their jurisdiction to the secular courts. These events were seen as marking the beginning of a series of reforms that would shake the foundations of the new state's social life. The old religious establishment found itself in opposition to the new secular measures. Other elements in Turkish politics opposed them from a non-religious position. For many members of the opposition, it was not worth passing from constitutional monarchy to absolutist republic. Most of the leading nationalists, who had played a decisive role in the War of Independence, were now in opposition to Mustafa Kemal. The most important resistance to the regime came from the Kurdish minority in this period. When the Turkish Republic was created, its citizens were faced with the problem of identity. The population was predominantly Muslim because most of the non-Muslim people of Anatolia had fled Turkey as a result of the conflicts between 1913 and 1923, and the transfer of populations agreed to at the Lausanne Conference largely completed this process. The population of the new Turkish state was, however, ethnically still mixed, with the Kurds being the largest minority group. The official identity of new Turkey had to be constructed through yet more ethnic conflict, this time with the Kurdish citizens of new Turkey. On 29 October 1924, the Grand National Assembly in Ankara accepted a new constitution and declared the new Turkish state a republic. The constitution forbade the use of Kurdish in public places. Law number 1505 made it possible for the land of large landowners to be expropriated and given to the new Turkish settlers in Kurdish areas. The geographical term 'Kurdistan' (land of Kurds) was omitted from all educational books and Turkish geographical names were gradually substituted for Kurdish names throughout the country. All of these measures contributed to the already existing dissatisfaction among the Kurdish population with the new regime in Turkey. The first Kurdish uprising since the proclamation of the republic, that of Sheikh Said, occurred in February 1925. It took a full-scale military operation to put it down. The consequences of the rebellion for Turkey, however, were far more important than the rebellion itself. The rebellion gave the leaders of the Turkish Republic an opportunity to silence the opposition. It created and provided a means whereby most serious subsequent opposition to government policies or comprehensive disagreement with its progress laid open the possibility that the disaffected groups would be labelled as traitors. In March 1925, the government made the parliament vote on the notorious Law for the Maintenance of Order. This marked the definitive establishment of the monoparty regime in Turkey. At the same time, itinerant extraordinary tribunals known as Courts of Independence were re-established. They had already raged during the war of independence. They operated for two years, sentencing 600 people to death. Andrew Mango knows this history well, and as the author of an admirable biography of Ataturk he is a veteran and sympathetic observer of the Turkish scene. His Ataturk: The Biography of the Founder of Modern Turkey (1999) still constitutes the definitive account among many other works and reveals a wide range of complicated aspects of its subject, showing us a far more complex, and interesting, personality than we had seen before. In From the Sultan to Ataturk: Turkey too, Mango's focus is very closely on Mustafa Kemal himself. Within its confines, this book is clearly and elegantly written, and comprehensive, and is based on an extensive array of printed Turkish sources. The picture Mango gives us of the emergence of modern Turkey is a compelling one. The result is a more textured and complex picture than has hitherto been available. -- Bulent Gokay H-Diplo Review 20110318

ISBN: 9781905791651

Dimensions: 25mm x 15mm x 2mm

Weight: 454g

240 pages