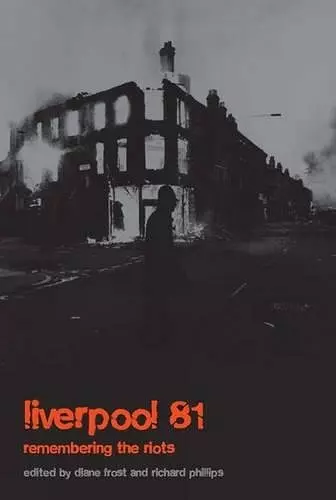

Liverpool '81

Remembering the Riots

Richard Phillips editor Diane Frost editor

Format:Paperback

Publisher:Liverpool University Press

Published:9th Jun '11

Currently unavailable, our supplier has not provided us a restock date

In July 1981 a series of street disturbances that took place in the Liverpool 8 area of the city put Liverpool at the forefront of events that also rocked other communities as far away as Brixton and Birmingham. After four days of riots, 150 buildings had been burnt down and countless shops looted, 258 police needed hospital treatment and 160 people had been arrested. Six weeks later, when the disturbances died down, 781 police officers had been injured and 214 police vehicles damaged. Few of the injuries to the rioters were officially recorded but some came to public attention with powerful consequences. Published to mark the 30th anniversary of what became known nationally as ‘the Toxteth Riots,’ Liverpool ’81 draws together memories of and responses to the 1981 riots from the people who were there. The book explores why the riots took place and what their consequences and legacies have been for Liverpool. It goes on to ask what has become of the people and places most directly affected by the riots – Black and Minority Ethnic communities, and residents of what were then labelled Inner Cities, not just in Liverpool but further afield – and how these communities have reacted to and moved on over the past 30 years. Combining fascinating interviews with rioters, police and community leaders with never before published photographs, Liverpool 81 tells the story of one of the most explosive summers in recent British history. All royalties from this book will be donated to the Merseyside Black History Month Group Ltd initiative.

In July 1981, some of the most violent rioting ever seen in Britain erupted in the Toxteth area of Liverpool. Thirty years on, the local community is still paying the price. After the second night of fire and rage, police burst through the door of the Simon family home in a little terrace along Beaconsfield Street in Liverpool, snatched 13-year-old Michael and flung him on to a pile of other young bodies packed into the back of a van. "I thought I was going to be killed," recalls Michael. "There were 10 in the van and I was on top - only a small, thin lad, taking most of the beatings. They beat me until I could hardly feel it any more and I thought that was it for me." Michael was one of 500 people arrested over nine nights of wrath - three decades ago this weekend - during which 470 police officers were also injured, a disabled man was killed by a police vehicle and 70 buildings incinerated. The so-called "Toxteth riots" of July 1981 were the most virulent single uprising on the British mainland within living memory, and have been considered the most far-reaching. "Back then," says Michael Simon, "you saw it from where you stood: I was 13 years old, and from my point of view, it was about police brutality, which was invariably racist. Only with hindsight did we realise that it was about the machine, the system, the whole thing." Michael was born in Beaconsfield Street, one of six, to a father from Liverpool of west African, Antiguan and Irish descent and a Scouse-Irish mother. His father worked as an electro-plater for Triumph and Ford where the chemicals he handled preparing chrome badly damaged his health. For the boys in the family, says Michael, "harassment by the police was a daily thing, especially for the boys older than me. My older brother, our Brian, was forever being beaten up by the police; not even arrested sometimes - just beaten up. One time he was accused of robbing lead from a roof, and my mum had to go down the street and jump on top of him so he wouldn't get battered, and she got arrested too." Michael Simon's mother, Mary, has been rehoused now to a new home in the heart of Toxteth. The homestead is all coming and going of a morning, Mary's daughter Karen making tea in her hospital staff tunic before Michael and his brother swing round. Although I was younger and had paler skin than Brian," says Michael, "I still got picked on. I remember one time I was getting on the bus at Lodge Lane after school, with my brown leather sports bag. A car had been robbed and the police pulled up in a van and grabbed me off the bus and started going through my bag. And I thought: 'If a car's been robbed, what's that got to do with my bag?'" After the riots, however, "in the immediate aftermath, we'd lifted the fear. We'd established a no-go area. We were too powerful even for the police." The insurgency, he says, had erupted from "a new confidence in our identity; we had nothing to apologise for". Like the anniversary of any tumultuous occasion, that of the Toxteth riots has many, often conflicting, voices and histories, and tomorrow a book is published - Liverpool '81: Remembering the Riots - that seeks, says one of its editors, Richard Phillips, "to hear some of the unheard voices" (of which Michael is one). The book coincides with the opening of an exhibition this weekend at Liverpool's Museum of Slavery, at which a collection of unseen pictures of the riots will be shown, taken by unknown photographers and donated to a law centre that opened in their wake (now closed). It is curated by the Merseyside Black History Initiative and Sonia Bassey Williams, who herself grew up, she says, "in a street where you couldn't stand outside your own home without the police threatening to arrest you for soliciting. I was 15, and had to go and look up what 'soliciting' meant." From the establishment's point of view, the riots were an alarm call said to have changed the face of policing in Britain and led to what national and local authorities have since called the "regeneration" of the inner cities. But as Michael Simon and I walked down Beaconsfield Street last week, we did so through an urban graveyard: the home from which he was wrenched by the police in 1981 boarded up and condemned, like almost all the others, for 18 years. What politicians since the riots have called "regeneration", Michael and his one-time, now scattered, neighbours call "degeneration"; plans with names such as "New Heartlands" are known here locally as "New Heartbreak". Even the riots themselves have two names: as with the names "Londonderry" and "Derry", you declare yourself. "People say 'Toxteth riots' or 'Liverpool 8 uprising' depending on their politics," says Michael. The label locating "Toxteth" rather than "Liverpool 8" was that of the national media at the time, he says, because of a sign on Princes Avenue, opposite a drive-in bank and what was the Rialto furniture store, both famously targeted and gutted by fire in 1981. The summer riots of that year - during which CS gas was used for the first time in the UK outside Northern Ireland - were the latest in a series of insurgencies, beginning in St Pauls, Bristol, during 1980. The following year, between 10 and 12 April in Brixton, south London, black youths fought the police and burned buildings, and in early July there were violent clashes between Asian youths and racist skinheads in Southall, west London. Within days of the uprising in Toxteth, a police station was attacked in Moss Side, Manchester and between 11 and 12 July, disturbances and riots were reported from 20 places, including Leeds, Hull and elsewhere. Underpinning these outbreaks were the themes of discrimination against black people in an increasingly precarious economy, bitter hostility in the inner cities to the government of Margaret Thatcher and several years of assaults on black and Asian communities by the National Front, which had in turn provoked the formation of the Anti-Nazi League, street-fighting by anti-fascists and, in 1977, the "Battle of Lewisham" in London. The 1976 Notting Hill carnival had ended with running battles between the police and black youths chanting: "Soweto, Soweto", after the uprising there and repressions in apartheid South Africa earlier in the year. Strong cultural currents flowed through the period, including the influence of American ghetto soul music, and arrival of songs by Bob Marley. "It's easy to look back through rose-tinted spectacles," says Michael now, "but in the 1970s, there was a real confidence within the culture that something could be done." But the overt reason for the serial disturbances was the ubiquitously appalling treatment of black youths by the police. Harassment, intimidation and wanton arrest were integral to the fabric of young black life, invariably applied by flagrant abuse of the so-called suspected persons, or "sus" law, a section of the 1824 Vagrancy Act that permitted police officers to arrest anyone loitering "with intent to commit an arrestable offence" - which in Britain's ghettoes had come to mean almost anyone between the ages of 13 and 30. "David" - not his real name - is a community activist who was born in the predominantly white Park Road area of Toxteth, the second youngest child of a father who had been a sailor from Guyana and retrained as a toolmaker, while his mother was Welsh/Irish, from Liverpool. With such quintessential Scouse lineage, David says: "I'm mixed race but I don't refer to myself that way. I'm comfortable with describing myself as black British." He recalls: "Growing up in the 70s, there were black gangs that used to fight the white gangs, but we lived in a white area. My mum was white and my dad was black so you would be caught in the middle. And I went to a black school, stuck in the middle of it all. So I did not know what this fighting was about, but slowly became aware of what racism was when people from time to time would call me a nigger, coon, wog... the list went on." However, says David: "I'd constantly be stopped because I lived in a white area, generally on the basis of 'What are you doing here?' I remember an incident regarding my brother. It was back in the late 70s, and we were all pigeon mad. It was a craze like the Rubik's Cube, skateboards and BMX bikes: pigeon pens, and pigeons. I remember my brother had gone out one morning with two of his white friends looking for pigeons. When I eventually got to speak to him and asked him what had happened and how he came to be arrested, he told me that when the police first ran after them they were shouting to others that joined the chase to grab 'the black one'. They caught all three of them and then proceeded to let the two white lads go." David recalls: "We soon learned that the only place where there was any visible racial equality in Britain was either in the job centres or in prison, and there were as many whites rioting in 1981 as there were blacks, because having the postcode L8 could stop you getting a job even if you were white. There were white people being subjected to the treatment being dished up to us. When these race wars back in the 70s were over, the community - although fragmented - started to mix, and people would get to know each other." Although the uprising in Liverpool shared many underlying causes with those elsewhere, there were crucial, deep-rooted singularities, to do with the city and its history, and the unique make-up and origins of its black community. Michael Simon says: "There was a kind of hybrid pride in being a Liverpool-born black. The identity was black, but it was 'Liverpool-born black'. I don't remember thinking that we were taking up what was happening in London - in fact, people came up from Brixton, and I remember one man saying it was 'full of red men' up here, meaning mixed-race people, like he didn't think we were proper black people." The conversation shifts, as it invariably does - and importantly - in Liverpool 8, back to the history of the city and its black community, the key to understanding why Toxteth was the most violent of the insurgencies of 1981, and, over the long term of 30 years, the most thoroughly punished. "I mean, it was obvious, even to me at the age of 13," says Michael, "that if it's all about cohesion and integration, then Liverpool 8 should have been a shining example, par excellence. But it wasn't - the discrimination was worse here than Manchester or anywhere else. Why wasn't it the shining example? Well, it's what [sociologist] Paul Gilroy writes, isn't it? That complex: mixed-race kids remind the greater part of a racist society about the union of black and white, and they just can't handle it." All riots and urban insurgencies have far deeper roots than newspaper headlines afford them, and those in Liverpool 8 stretch further into history (and geography) than most. There is first the singular history of Liverpool itself, and what the city's leading historian, John Belchem' pro-vice chancellor of the university, calls the "exceptionalism" that marks Liverpool out from the rest of Britain, stitching its narrative to the Atlantic Ocean more than that of the land on which Liverpool turns its back. This identity is precious to the sage of Liverpool and most immediately recognisable voice of the city's people, Jimmy McGovern, known for his work on Brookside, Cracker, Hillsborough, The Street and the rest. "When you are a port city," says McGovern, "you look out, not back inland over your shoulder. Only when you are at sea are you looking towards the land, as my own family did when they came here from County Fermanagh; probably heading for America but presumably alighting with a certain fecklessness: 'This'll do.' And in Toxteth, you have the Harlem of Europe. When we had the capital of culture here in 2008, the slogan was 'The World In One City', but that was only really true of Liverpool 8: black people called Riley and Williams, Irish women bearing children to West African sailors, and all of them, in some way, children of the sea." Then there are the origins of what are called "Liverpool-born blacks", of which Michael Simon's and David's rich lineage is typical. It is an epic narrative in its own right and one that belongs to - as the title of a famous book by Paul Gilroy calls it - "the Black Atlantic", and all its shores from which slaves, migrants and seamen sailed: African, American, British, Caribbean - and even, in the case of Liverpool, Irish and Welsh. It is a narrative that led American academic Jacqueline Nassy Brown to conclude after an exhaustive survey of so-called "LBBs" that reference to a "black community" in Liverpool does not always mean black people, and it explains why Michael was often called "that blond Afro kid". "If you were black, you went to sea," says part-time university lecturer Mike Boyle, sipping a pint with others who were - like him - laid off at some point from Merseyside's factories and shipyards. Boyle progressed from the streets of Liverpool 8, via work at Plessey, to become a historian of this singular community, and thereby the deep roots of the 1981 riots. He traces his ancestry to west Africa, the slave plantations of Barbados and Ireland, but grew up in Liverpool 8, a truly fine citizen of this black/green/Scouse Atlantic. "My great-grandmother was a Fenian in Dublin," he says, "and Grandfather Boyle moved to 135th Street in Harlem." Back in Liverpool, however: "My great-grandfather on my mother's side was a qualified ship's captain, but was never allowed to sail out of Liverpool as such, because the crews would not take orders from a black captain. My father was an engine-room foreman - a 'donkey-man' - in the merchant marine, but when he applied for a job with Cunard, he was told: 'We have to consider our American passengers', and that was it, no work, even though he pointed out to them that the 'American passengers' would never see him. He had sailed to Brazil and Argentina; he was a man of the world, but his was the last great seafaring generation of the city." Liverpool 8 never has been the poorest part of the city. That would be the north side, and hinterland behind the docks, economically savaged by the gradual closure of Liverpool's mighty port, despite serial resistance by one of the most stalwart movements in British labour history. The dockside was mainly white work, though the crews were black, and both suffered as seafaring ceased to be Liverpool's pride and grind. As work at sea declined, blacks like whites sought other work, Mike Boyle too. Liverpool 8 lives cheek-by-jowl not only with the sea but with the city-centre shops, where young Mike tried to find work as a window-dresser, and was given a job, only to be told when his boss returned from headquarters: "'I'm sorry, but when you are in the window, you represent the company.' I was 17 years old." "Yes," says David, "I was in the riots. I remember thinking at the time that these bizzies or...

ISBN: 9781846316685

Dimensions: unknown

Weight: unknown

150 pages