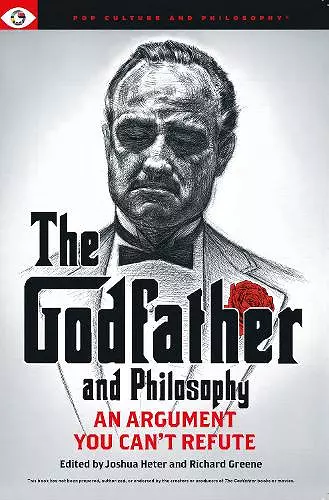

The Godfather and Philosophy

Richard Greene editor Joshua Heter editor

Format:Paperback

Publisher:Carus Books

Published:7th Sep '23

Should be back in stock very soon

The Godfather and Philosophy is comprised of twenty-eight chapters by philosophers, who reflect upon the ethical and metaphysical issues raised in The Godfather novels and movies, beginning with the 1969 novel by Mario Puzo and the 1972 movie by Francis Ford Coppola.

The Godfather saga has had a profound impact on American cinema, storytelling, thinking about crime, and popular culture. Aimed at thoughtful fans of The Godfather franchise, among the questions tackled in these provocative philosophical chapters are the immigrant experience in America, the relation between ethics and the law, the nature of moral corruption, private justice and vigilantism, organized crime and the American Dream, betrayal and forgiveness, religion and family values, the difficulties of breaking out of a dysfunctional way of life, and the uncertain consequences of vice laws.

Joshua Heter teaches philosophy at Jefferson College, Missouri. He co-edited Punk Rock and Philosophy (2022).

Richard Greene teaches philosophy at Weber State University, Utah. He wrote the definitive and highly acclaimed book, Spoiler Alert! (It’s a Book about the Philosophy of Spoilers) (2019).

A fascinating, thought provoking, and fun read from cover to cover, "The Godfather and Philosophy: An Argument You Cant Refute" will have an enormous appeal to Godfather fans and readers with an interest in popular culture, social science, and philosophy. While especially and unreservedly recommended for personal, professional, community, college, and university library Philosophy & Popular Culture collections and supplemental curriculum studies lists, it should be noted for students, academia, and non-specialist general readers with an interest in the subject that "The Godfather and Philosophy" is also available in a digital book format

James A. Cox, Editor-in-Chief, Midwest Book Review

In a Woody Allen short story called “The Kugelmass Episode,” the title character, a professor of Humanities at City College, escapes a loveless marriage by being transported into the novel Madame Bovary as Emma’s lover. On encountering an unrecollected character kissing Emma on page 100 of his text, a Stanford professor remarks to himself that it just shows you can reread a great book a thousand times and still find something new. I bring this story up because, having co-edited several volumes in the Popular Culture and Philosophy Series (full disclosure, one of these was with the co-editor of the current volume under review), the figure of Kugelmass offers an image of what I see as a guiding goal of such volumes—and boy are there a lot of such volumes! Whatever the subject of ‘X’ in the title “X and Philosophy,” the readers of these volumes, who are invariably extremely familiar with the subject matter, should experience the same sense of surprise as the Stanford professor did with Madame Bovary, with philosophy serving as the new character introduced into their favorite work of art. In order to facilitate this experience, an editor as well needs to keep in mind another fictional figure, Goldilocks, and get the dosage of philosophy just right. Too much and you can turn the reader off, too little and you fail to light the flame of their curiosity. Invariably, philosophers who submitted papers for the volumes I edited erred on the side of intricacy, and a large part of the work of editing was weighting the essay in the other direction. A just right essay starts where the reader is, philosophically speaking, and then escorts them on a journey to new, hitherto unexplored intellectual territory. A good example of getting it just right in the volume Godfather and Philosophy is “Loyalty as Omerta.” Most readers of this essay will no doubt start with the assumption the loyalty in general is a good thing as far as it goes but that it can easily go too far—and does so in The Godfather, as what seems to be misplaced loyalty results in the commission of crimes and the creation of conditions that in general are harmful to society. As a counterweight to common assumptions about loyalty Alexander Hooke brings in the philosopher Josiah Royce, who viewed loyalty as the foundation of the good life, taking us “out of the citadel of individualism to commit to something greater” (31). Given the value placed on loyalty in the world of The Godfather, where do the mobsters go wrong—or do they? The point is not to settle the issue once and for all but to raise questions in readers’ mind, questions that they can bring to yet another viewing of or reflection on the movie.

Another way to hit the philosophical sweet spot besides examining basic moral assumptions is to pose a “big” question about the work—one that is deeply philosophical but which everyone who has experienced the work has an opinion about, thus demonstrating to the reader that they are already engaged in the practice of philosophy. “Does Vito Corleone Live a Good Life?” by Tim Dunn does an excellent job of this. Using Aristotle’s concept of the good life as the standard, Dunn points out that Aristotle defined happiness as an activity of the soul in accordance with virtue. If we bring to the table a Christian account of virtue, it would be obvious that Vito is not virtuous and hence could not be happy. But Aristotle is not Augustine, and Dunn makes a strong case that Vito can be seen as exhibiting Aristotelian virtue. According to Aristotle there are two types of virtue: intellectual virtues and character virtues. By intellectual virtues Aristotle does not mean “book smarts” but a state translated as practical wisdom and which could certainly encompass “street smarts.” This Vito has in abundance, as Dunn demonstrates by reviewing many of the moves Vito makes that obviously required deliberation and foresight. For example, after Sonny is killed, he calls a meeting of the five families to negotiate a truce. And after Michael’s return, he prepares the ground for his succession. Nor is Vito lacking in Aristotle’s character virtues: Courage, magnanimity, and generosity are key Aristotelian virtues which Vito exhibits in abundance. Indeed, Dunn’s denial that Vito lived a good life is far less convincing than his apologia. In large part, Dunn denies Vito a good life based on his inability to form the sort of ideal friendships that Aristotle saw as an inherent part of the good life. For Aristotle, this ideal friendship is the friendship of those “who are good, and alike in virtue . . . and they are good themselves” (NE VIII.3). This type of friend is “another self.” To say the least, this is a rather high bar to clear for entrance into the good life. Aristotle himself admits that such friendships are rare. Hence, if Vito is not happy because he lacks an Aristotelian other half, then very few people are happy. A second argument Dunn uses to deny Vito a good life is his refusal to believe Vito’s claim that he has lived his life without regret. Dunn asserts, “If he truly had no regrets about his life choices, why would he not want Michael to follow in his footsteps?” This seems a non sequiter. Why does wanting more for your children mean you have regrets about your own life? I have known many blue-collar parents who both sincerely and believably profess no regrets in how they have spent their lives but who wish for their children a very different existence. Like Vito, they accept with equanimity that they were unable due to circumstances to follow the path that they were able to make available for their children. However, the point, again, is not to definitely settle the matter for the reader but to engage the reader in the debate, which this essay does marvelously.

Readers will get a heavy dose of the history of philosophy, with roughly half of the essays in this category, while ethical and political thought make up the next two largest groupings. Three essays I cannot classify because I refuse to read them concern Godfather III. (You may recall the scene in Arthur, where a drunk Arthur comments to his soon-to-be-father-in-law about the stuffed moose on the wall, “You must have really hated that moose.” Yes, I really hated Godfather III).

I have only a couple of quibbles with the volume, one that was likely outside the editors’ control and another which, as far as I can tell, they bear full responsibility for. As someone whose area of specialty is ancient philosophy, far be it from me to complain about five essays devoted to Plato. But to have them all focus on the Republic seems a wasted opportunity. Plato did write other dialogues, some of which offer rich material for The Godfather. The Crito, where Socrates explains to those who wish for him to escape why his obligation to the state trumps all other motives, would have been a fascinating vehicle for exploring the nature of our obligations—to the state, our family, our friends, ourselves, and the truth—among the characters in The Godfather. And to discuss Beauty in the context of a Platonic dialogue and not bring up the Symposium, as occurs in the essay “An Offer Michael Should Have Refused,” is a bit like discussing The Godfather and not mentioning Francis Ford Coppola. Which brings me to my second quibble, since this is precisely what the editors do in their introduction to the volume. While I can admire their focus on the author of The Godfather novel, whose contribution to Godfather legacy is no doubt overlooked, and endorse the claim that The Godfather movies would not have come into existence without Puzo’s work, it’s also true that the Sistine Chapel would not have come into existence without the Bible. But Michealangelo, I think, would earn a reference in any work about that architectural structure, and Coppola merited at least a shout out from the editors in their introduction.

But this is a small injustice (especially, say, compared to the one that Amerigo Bonasera experiences at the start of the novel), and should not dissuade one from picking up The Godfather and Philosophy, which is long-overdue, well-executed, and deserving a place on the bookshelf of every true Godfather aficionado.

Peter Vernezze, Journal of Film and Philosophy

ISBN: 9781637700372

Dimensions: 228mm x 152mm x 12mm

Weight: 453g

280 pages