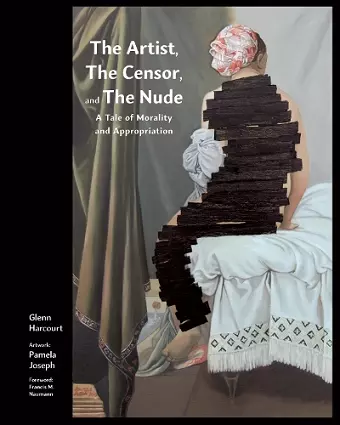

The Artist, the Censor and the Nude

A Tale of Morality and Appropriation

Format:Hardback

Publisher:DoppelHouse Press

Published:26th Oct '17

Currently unavailable, our supplier has not provided us a restock date

A unique commentary/critique combining art history, feminism, painting and observations about the culture of censorship in Iran and the West.

This hybrid book examines the art and politics of “The Nude” in various cultural contexts, featuring books of canonical western art pirated and either digitally- or hand-censored in Iran by anonymous government workers.

Author Glenn Harcourt uses several case studies brought to the fore by American painter Pamela Joseph in her recent “Censored” series. Harcourt’s rigorous, culturally-measured and art historical approach complements Joseph’s appropriation of these censored images as feminist critique. Harcourt argues that her work serves as a window toward larger questions in art. These include an examination of the evolution of abstraction; the role of women in western society, as seen through the history of painting the body; the effects of western art on cultures outside the west (sometimes referred to in Iran as “west-toxication”); and how artists in non-western countries, specifically those in Iran living under rules of censorship that specifically prohibit representation of the body, engage with the history of western art found in the censored books.

Harcourt’s discussion of Iranian contemporary artists focuses on censorship tropes in portraiture, including works by Aydin Aghdashloo, Gohar Dashti, Katayoun Karami, Daryoush Qarezad, Manijeh Sehhi, Newsha Tavakolian, and others. Issues of privacy and security prevent some Iranian artist insiders from being named, but studio images as well as recipes for removal of the censored marks along with testimony from artists who are now living outside Iran provide reference for many English-speaking readers who don’t otherwise have knowledge of the country’s strict policies.

Image reproductions ranging from the pages of the censored books themselves, to Joseph’s paintings, to artwork by contemporary Iranian artists, make the book visually intriguing, timely, and visually fascinating reading.

I applaud the originality and complexity Harcourt has brought to the topic. Given Joseph’s long artistic history of a humorous and feminist point of view in her work, the technique involved in her dedicated recreations of Iranian censorship of Western art insists on the artificial and paradoxical significance of the experience between the live viewer and the two-dimensional artistic plane. Where in that engagement is the temptation, where the agency, and what, ultimately, is the censor able to censor? Is it rather the case that the power of art to arouse and provoke is being highlighted and enhanced? Additionally, as a historian of women and gender studies, I find that the book provocatively opens the question of the relationship between a Western artistic canon and Iranian Muslim viewers, how it is mediated by censors as representatives of the state and official culture, and to what extent any of these subject positions (artist, viewer, state, censor, critic) is assumed to be gendered masculine. The mere critique of the concept of Orientalism is not sufficient here. Joseph’s art and Harcourt’s analysis of her work and of (predominantly) Iranian artists remind the reader that there is no such thing as either a monolithic Western or Islamic viewpoint or identity. Rather, these are contingent, multiple and shifting, on both sides of any attempted binary divide between Western and Islamic or masculine and feminine. I quite revel in the evidence provided that a feminine—or feminist—point of view can so thoroughly disrupt our expectations and experience of art and culture that we thought we knew.

– Molly Tambor, Associate Professor of History, Long Island University

Of all the many books that have been published about Iran, none so viscerally conveys the absurdity of the censorship that bears on the nation, or the spirit of rebellion against it as The Artist, the Censor, and The Nude. Only an artist of the keenest sensibilities, like Pamela Joseph, can make such a distant experience so present.

– Roya Hakakian, author of Journey from the Land of No: A Girlhood Caught in Revolutionary Iran

Pamela Joseph understands the power of image. By manipulating such icons as Magritte, Rousseau, Courbet, Dali, and Duchamp, the new adaptations are not only outrageous and humorous, but laced with absurdist dark humor.

– BOMB online

Thoughtful and rigorous, the book provides an excellent survey of contemporary censorship.

– Publisher's Weekly

It’s no secret that Glenn Harcourt is a triple threat: he’s first rate as a graceful (and rigorous) writer; an art historian, and a cosmopolitan intellectual. All his talents are on display in The Artist, The Censor, and The Nude. “Erasure” is a common enough theme in both art history and critical studies, but it becomes a particularly potent subject when discussing Iranian art and culture, and by extension, contemporary art in the so distant Islamic world. The fun of Harcourt’s piece is his coupling of Islamic pudeur and post-modernity’s blank ironies. Pamela Joseph’s work provides an excellent jumping off place for juxtaposing Islamic modesty and post-modernity, without getting into tedious neo-Marxist mea culpas on the guilt of western orientalisms, or for that matter, of middle eastern occidentalisms. Harcourt has a keen eye (and a light sense of irony) for appreciating those conjunctions, but the real depth of Harcourt’s work is his brilliant juxtaposing of the two. And to do this all, while providing an excellent survey and analysis of the human body as a universal subject for art-making, makes this book a real tour de force.

– Donald Cosentino, UCLA Professor Emeritus, World Arts & Cultures/Dance

ISBN: 9780997003420

Dimensions: unknown

Weight: unknown

128 pages