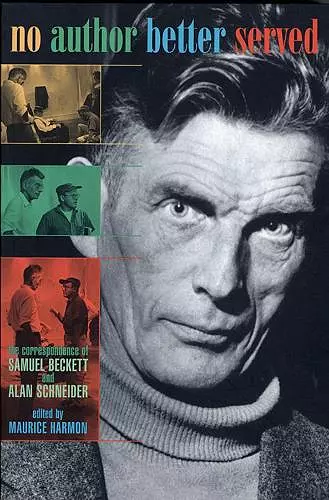

No Author Better Served

The Correspondence of Samuel Beckett and Alan Schneider

Samuel Beckett author Alan Schneider author Maurice Harmon editor

Format:Paperback

Publisher:Harvard University Press

Currently unavailable, and unfortunately no date known when it will be back

For Alan Schneider, directing Endgame, Samuel Beckett lays out the play’s philosophy, then adds: “Don’t mention any of this to your actors!”

He claimed he couldn’t talk about his work, but Beckett proves remarkably forthcoming in these pages, which document the thirty-year working relationship between the playwright and his principal producer in the United States. The correspondence between Beckett and Schneider offers an unparalleled picture of the art and craft of theater in the hands of two masters. It is also an endlessly enlightening look into the playwright’s ideas and methods, his remarks a virtual crib sheet for his brilliant, eccentric plays.

Alan Schneider premiered five of Beckett’s plays in the United States, including Waiting for Godot, Krapp’s Last Tape, and Endgame, and directed a number of revivals. Preparing for each new production, the two wrote extensive letters—about intended tone, conception of characters, irony and verbal echoes, staging details for scenes, delivery of individual lines. From such details a remarkable sense of the playwright’s vision emerges, as well as a feel for the director’s task. Of Godot, Beckett wrote to Schneider, “I feel my monster is in safe keeping.” His confidence in the director, and Schneider’s persistent probing for a surer understanding of each play, have produced a marvelous resource: a detailed map of Beckett’s work in conception and in production.

The correspondence starts in December 1955, shortly after their first meeting, and continues to Schneider’s accidental death in March 1984 (when crossing a street to mail a letter to Beckett). The 500 letters capture the world of theater as well as the personalities of their authors. Maurice Harmon’s thorough notes provide a helpful guide to people and events mentioned throughout.

Though this 30-year correspondence between Samuel Beckett and theater director Alan Schneider will mainly be read by Beckett buffs, there is much to interest a wider audience… Proposals scotched by Beckett included a radio version of Happy Days with Edith Evans and a film of Godot by Roman Polanski. This epistolary friendship ended in 1984 when Schneider was killed while crossing a road to mail a letter to Beckett. -- Emma Hagestadt and Christopher Hirst * The Independent *

[An] absorbing edition of the correspondence between the playwright and the director. -- Fintan O’Toole * New York Review of Books *

[Samuel Beckett’s] disdain for critics is among revelations in [this] extraordinary collection of more than 500 letters… The 30-year correspondence between Beckett and Alan Schneider, who staged the American premieres of dramas such as Waiting for Godot…is virtually a history of Beckett’s growth as a dramatist. The letters are all the more significant because Beckett rarely discussed his work in public, dismissing questions with comments such as, ‘I meant what I said.’ The letters offer an unparalleled insight into the playwright who died in 1989 at the age of 89 and influenced writers from Harold Pinter to Tom Stoppard with his poetic pessimism and explorations of the big questions of human existence. -- Dalya Alberge * The Times *

The playwright was always adamant: productions should follow his stage directions explicitly. In a new book, No Author Better Served, a collection of 30 years of letters between Beckett and his director Alan Schneider, the playwright offers fascinating insights about performance and interpretation if not meaning. -- Mel Gussow * New York Times *

[No Author Better Served] has been edited with a useful introduction and great textual care… Beckett’s letters often reveal not only his uninterrupted faith in Schneider but a charming modesty, an engaging self-deprecation… In return, Schneider, often using gloomy phrases from Beckett’s plays, sends his friend his despairing reflections on the state of the American theater, American culture and American politics. -- Robert Brustein * New York Times Book Review *

Because the world of Beckett’s plays is so stark and desolate, many assume that he was, too—aloof, cold and somber. But No Author Better Served…reveals a different portrait of a writer… The letters show not only a demanding artist but also a kind and gentle man… This epistolary dialogue reveals a playwright’s vision that gradually transformed our sense of the world and ultimately won the 1969 Nobel Prize for Literature. The correspondence also shows Schneider’s importance in developing and implementing that vision. -- Lisa Meyer * Los Angeles Times *

Beckett was adamant about not wanting his letters published, but Beckett was frequently wrong (‘I cannot help feeling,’ he writes, ‘that the success of Godot has been very largely the result of a misunderstanding’). Whatever was personal has been excised from the 500 missives that make up this book, but what remains includes vivid and often revelatory material about his interpretations of his own work. Schneider, who introduced many of the masterworks to this country, as an able and often provocatively inquisitive correspondent. The result is an enlightening volume that closes with a Beckettian twist: Schneider died in 1984 in an accident as he was crossing a street to mail a letter to Beckett. * San Francisco Examiner *

The letters to Schneider are overwhelmingly concerned with the details of the production and reception of Beckett’s plays in America. About these matters they are packed with information, making this an indispensable work. -- Hugh Haughton * London Review of Books *

This is a good-hearted book compiled, unwittingly, over 30 years by two very good-hearted people. The playwright who changed the course of twentieth-century drama exchanged regular letters with his adoring director in America. And their letters are gathered here together like a long and tender conversation… At the beginning and at the end of the game, Sam is always funny. In his despair, there is a chuckle; in his blackest threnodies, a modicum of wit… Read it if you love Beckett—and even, more importantly, read it if you don’t… The spirit of these two good men will protect the future from the grey and miserable nonsense that many academics try to wrap round Beckett. -- Peter Hall * The Observer *

The great virtue of this correspondence is that Beckett, especially in the years between Godot and Film, offers Schneider as much help in matters of interpretation great and small as any director could possible have expected. What Beckett called ‘the making relation’, emphasizing that this was the only (and itself a tenuous) relationship he could have with his own work, is here presented in unprecedented and unparalleled detail, so that no interpreter, on the stage or on the page, will be able to ignore it. Almost all Beckett’s plays can be seen in a new light in this correspondence, but there are particularly extensive entries on Waiting for Godot, Krapp’s Last Tape, Happy Days, Play, and Not I, and almost an overplus of detail when it comes to the 1964 version of Film with Buster Keaton. Schneider’s letters on their own would be valuable as a record of a great director working all over the world with great (and, more often, not so great) actors and technical staff. But, not surprisingly, it is Beckett’s phrases that stay in the mind. -- John Pilling * Modern Language Review *

Beckett’s responses…are always entertaining and often enlightening. The book is sure to become required reading for graduate students and is a must for anyone interested in staging any one of Beckett’s self-proclaimed ‘monsters.’ -- Chris Davis * Memphis Flyer *

It is only with the publication of the correspondence, of which that with Schneider is a small yet vital part, that the extent of Beckett’s investment in the practicalities of the world can be fully appreciated. He was one of the great letter-writers of our era, indeed of any era: not just by the volume of his correspondents and letters…[but] by the extraordinary quality of his attentiveness, both to the person he was addressing and to whatever they were discussing. His letters have an utter lack of pretension or posture, reminiscent of Kafka’s in their luminous directness… What is unique about this correspondence is the fact that…both sides survive almost intact, a witness to thirty years of intense and fertile exchange. Schneider’s energy bristles on every page… Harvard University Press has done a fine job on this volume, leaving just enough blank page to let each letter breathe. The editor, Maurice Harmon, presents a virtually flawless text, having painstakingly transcribed what Beckett termed his ‘foul fist’, a hand so difficult that even Schneider often deciphered it in installments. Harmon provides a serviceable introduction, with an overview of the friendship, and his unobtrusive notes list the casts, theatres and principal reviews of the most important productions. -- Dan Gunn * Times Literary Supplement *

Emily Dickinson famously wanted her poems destroyed, a desire that, thankfully, was ignored. For similar reasons, one can only be grateful that Harmon—a professor at University College, Dublin—persisted in bringing to light an exchange that further illuminates Beckett’s prismatic genius. Gossip-mongers may be put off that there aren’t more personal revelations… What Harmon’s excavation invaluably offers instead is a record of a sustained creative partnership virtually unique in the postwar theater… For most readers the collection will be of interest as an insight into Beckett’s famously elusive and reluctant interpretations of his own gift. -- Matt Wolf * San Francisco Examiner & Chronicle *

Maurice Harmon’s scrupulously edited volume is absolutely essential reading for all students of Beckett and for anyone with even a passing interest in the terrors, ignominy and glorious rewards of theatre. The editor is to be complimented for his honouring of the Beckett Estate’s request for the exclusion from the letters of matter merely personal and private… Such editorial tact is rare and welcome. This is a volume to visit and revisit and deeply breathe of its ‘vivifying air.’ -- Gerry Dukes * Irish Independent *

Given that his characters have such a fractured, antagonistic relationship with the world, you might imagine Beckett himself to have been locked in a kind of manic Salinger-like seclusion. Not at all: the sense of the man you get from the letters here is of a highly considerate, friendly and decent human being—and one who has no more problems dealing with the quotidian than you or I… It is almost funny to think of Beckett in the real world; which is probably one reason why he was stalked by so many devotees, anxious to touch the hem of his garment. And it is why this correspondence, ably and tactfully edited, will be happily fallen on by academics, students, and cranky fans…who will recognise it as a motherlode of tangential information… There could be no comparable correspondence, I think, about [Beckett’s] prose. -- Nicholas Lezard * Sunday Times *

[These letters are] of particular interest in matters of Beckett’s stagecraft and self-interpretation… The notoriously demanding playwright favored Schneider, as Maurice Harmon explains in his concisely excellent introduction, because Schneider ‘did not intrude upon the work but submitted himself attentively to it, discovering its imaginative inner life’ …Scrupulous, too, is editor Harmon who supplies useful and thorough notes for each letter. Taken together, the Beckett–Schneider letters also offer a unique overview of Beckett’s stage work in the US… We are privy to their expert comments on the successes and failures of other Beckett productions here and abroad… A well-edited set of documents that will be uniquely invaluable to students of Beckett’s works and of the American theater. * Kirkus Reviews *

The playwright Samuel Beckett’s letters to his devoted American director reveal both an abiding affection for his longtime pen pal and an increasing rigidity and weariness of spirit. In 1999, the reviewer Robert Brustein said the book ‘not only chronicles the almost symbiotic relationship between a great writer and a faithful disciple but adds invaluable epistolary material to the Beckett canon.’ -- Scott Veale * New York Times Book Review *

ISBN: 9780674003859

Dimensions: unknown

Weight: 689g

512 pages