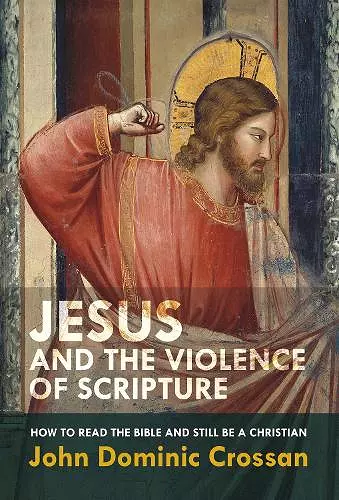

Jesus and the Violence of Scripture

Format:Paperback

Publisher:SPCK Publishing

Published:20th Aug '15

Should be back in stock very soon

A world-renowned scholar explores and explains the two views of God in the Bible – the violent God of vengeance and retribution, and the non-violent God who became incarnate in Jesus.

Which is the true Messiah – the peace-loving preacher of the Sermon on the Mount, or the sword-wielding warrior of the book of Revelation? And how can both be in the same Bible? In what is perhaps his most provocative book yet, John Dominic Crossan investigates two conflicting visions of God to be found in the Bible: one that offers unconditional love and grace to all humanity; the other working to domesticate that radical vision by threatening punishment and retribution, and by propping up the status quo. People often assume that the second vision applies to the God of the Old Testament, while the first was revealed later, in the teaching and example of Jesus. But, as Crossan shows, the same contradiction appears in the Gospels and other writings of the New Testament. One thing is clear, argues Crossan: if you want to discover the Bible's best and purest revelation of God, then you must measure the Bible by Jesus. And to find the best and purest revelation of Jesus, he concludes, you must learn how to distinguish the words and actions of the original, historical Jesus from the teachings of those who came after him, but who did not fully understand his radical message. Only then will you understand how to read the Bible and still be a Christian.

Praise for the author’s The Power of Parable: Crossan’s exceptional clarity and methodical presentation combine to make this one of the best, most enthralling Bible-study courses many readers will ever take. * Booklist *

We tend to ignore, explain away or filter out the violence attributed to God in the Bible. The phrase "Skeletons in the cupboard" comes to mind; critics of Christianity notice them and dig them out even if we don’t. "Ah," we say, "but that’s the Old Testament; the New is different." Yet violence is attributed to God in the New Testament as well. The provocative sub-title of John Dominic Corssan’s new book spells out the challenge: Jesus and the Violence of Scripture: How to Read the Bible and Still be a Christian. The author begins by telling us a bit about his own personal journey. An Irish Catholic, Crossan had joined a monastery by the age of 16 and began training for his priesthood soon afterwards. But the study of Thomas Aquinas, he says, taught him not only what to think, but also how to think. In 1968, by then in the States, he went public in his opposition to the papal encyclical Humanae Vitae on birth control. A rebuke from the cardinal archbishop of Chicago followed and, six months later, Cardinal Cody was still archbishop, "but Father Dominic (ie Crossan) was both an ex-monk and an ex-priest (p 5). Still a Christian, as his repeated, "we Christians" in this book shows, he became a leading authority on the historical background of Jesus and of Paul. And should you wonder whether this is too radical for a church house group, this book, the author tells us, has emerged from his talks in churches, not his lectures in the academy. The violence in the Bible is everywhere: not only a violent God, but a violent Jesus and a violent Paul (Crossan includes rhetorical violence – e.g. abusing opponents – on the charge sheet). And all this violence exists in the bible alongside a non-violent God, a non-violent Jesus and a non-violent Paul. How come? Civilisation and human culture, he argues, could not cope with the non-violence; it was simply too radical. The book has four sections: Part 1: Challenge introduces the argument; Parts II and III on Civilisation and Covenant look at the Old Testament evidence. Crossan is especially severe on Deuteronomy and related writings, which, in his view, turn the natural consequences of human wrongdoing into divine punishments. Part IV, entitled "Community," looks at the Gospels, Paul and Revelation – in which the non-violent first coming of Jesus becomes the violent second coming. But the Gospels are a problem too. The Jesus who taught "Love your enemies" (Matthew 5.44) is the Jesus who heaped vitriol on the scribes and Pharisees: "You snakes, you brood of vipers! How can you escape being sentenced to hell?" (p. 178). Years ago in the Epworth Review, former Methodist principal of Handsworth College Leslie Mitton pointed out the problem. Similarly, the Paul who wrote "In Christ there is … neither sale nor free, male nor female" (Galatians 3.28) is the Paul who wrote (or had attributed to him) "Slaves obey your masters," "Wives obey your husbands". Was this teaching a necessary compromise in the circumstances of the first century – or was it a sell-out? So in Crossan’s view the reaction against a radical God, a radical Jesus, a radical Paul, began very early – and it pervades our Bibles. He is scholarly, his arguments are brilliantly lucid and hi is passionately Christian. But is he right? Whether we’re talking about God, Jesus or Paul, there are problematic details – which our lectionary sometimes tip-toes around (A lectionary reading in two or three bits may be a sign that something unsavoury has been missed out). In both Testaments, the radical and the more conventional often co-exist in uneasy tension. But I wonder if Crossan’s solution in the end is both too neat and not deep enough. For example, on Genesis 4 he writes: "The mark of Cain is on human civilisation, not on human nature. Escalatory violence is our nemesis, not our nature; our avoidable decision, not our unavoidable destiny…" (p. 66). Jesus (and Paul) go deeper: "If you, being evil, know how to give good gifts…" (Luke 11.13). "The good which I want to do I fail to do…" (Romans 7.19). The current international scene demonstrates this only too well. Crossan’s central thesis appears simple: Jesus is the Bible’s centre, so evaluate the Bible in the light of Christ and evaluate all that it says about Christ in the light of the historical Jesus (p. 185). Compare our own Deed of Union: "…the revelation contained in Scripture… the supreme rule of faith and practice". Revelation, however, is a broader and deeper concept than the historical Jesus, of whom Christians have always tended to have different pictures and interpretations. For years (broadly speaking), the answers of both "liberal" and "evangelical" – if we must still use these unhelpful labels – to the thorny question of divine violence in the Bible have been inadequate. Liberals excise too much of Scripture; evangelicals tend to do the opposite. Crossan’s splendidly lucid book ought to make us think – and hopefully, enter more deeply into the mystery of "am essentially non-coercive God". -- The Rev Dr Neil Richardson * Methodist Recorder *

Those who do not read the Bible carefully – or who do not read it at all sometimes speak of a separation between the Old Testament God who is thunderous and cruel, and the New Testament God who is kind and gentle. It does not take long for such a reading to unravel, whether you are looking at the everlasting mercy of God in Psalm 103, removing our guilt with a separation as wide as East from West, to the frequent occasions when Jesus is quoted in the Gospels as predicting eternal punishment in an afterlife for the wicked. Indeed, the New Testament, which depicts Jesus the Prince of Peace riding into Jerusalem on a donkey, also allows a reprise in Revelation depicting Christ riding a celestial warhorse to take revenge on the Romans. Jesus and the Violence of Scripture is an attempt to explain the shocking contrast between these two positions. John Dominic Crossan’s subtitle – How to read the Bible and still be a Christian – begs a few questions. It implies that to be a Christian, you ought to agree with Crossan that there is no place in the Christian scheme of things for divine vengeance, or for the punishment of wickedness and vice. The compilers of the Book of Common Prayer, not to mention St Augustine, St Thomas Aquinas, or Dante Alighieri – to seize a few obvious examples – would not, by the Crossan criterion, be Christians. Those of us, however, who are disturbed by the violence of the biblical God, and of much notionally orthodox thought, will open Crossan’s book eagerly in the hope of some solution to our problems. Is it possible to excise from our picture of the biblical God the many instances where he is violent and encourages violence in others? Can we simply discard the God and Romans 1:18, for example, whose wrath "is revealed from heaven against all ungodliness of wickedness"? Or the God represented in Matthew 25:31ff, who will divide the sheep from the goats and send the goats to the "eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels", not to mention the bloodbath of Revelation 16:19, where "God remembered great Babylon and gave her the wine-cup of the fury of his wrath"? Could we manage to drop these bits out of the Bible altogether, and just keep the material about loving our neighbours and remembering the plight of the poor? And were we to do this, would we be what Crossan defines as "still… a Christian"? Crossan’s answer is yes. That is because his Bible is a supermarket where you have to read the labels of the wares on the shelves to avoid being hoodwinked into thinking you are getting the authentic stuff. Paul, in this reading, becomes an authentic messenger of the Kingdom-movement started by Jesus. "No betrayal of Jesus or Judaism was involved with Paul, who took Jesus’s vision out of the villages of the Jewish homeland and accurately rephrased it for the great Roman cities of the Jewish Diaspora." Some of Crossan’s most persuasive passages are those that point up what the original Paul thought about slavery, and what his followers or imitators wanted us to think he thought. There are seven authentic Pauline epistles – Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, 1 Thessalonians and Philemon. In Philemon, Paul addressed the owner of a salve called Onesimus. It is clear that Paul who proclaimed that in Christ there is neither bond nor free wanted Philemon to regard his former slave as a slave no more, but "a beloved brother" (verse 18). What explanation, then, do we have for those later injunctions, such as, "Slaves, obey your earthly masters with fear and trembling" (Ephesians 6:5)? For Crossan, the explanation is very simple. Paul did not write Ephesians. Crossan’s St Paul was in fact pro-women and anti-slavery – apart from an unfortunate outburst about women covering their heads while speaking. But, as Crossan points out this passage takes for granted that women did indeed speak in church to pray and prophesy (1 Corinthians 11:5). These points are well made, but for me they are a little too simply made. Crossan has set himself a very big task – namely to carve all the "authentic" bits out of the Bible, from Genesis to Revelation, and to discard the "inauthentic". His argument is premised on a conviction that the true God is always in favour of what Crossan sees as distributive justice. By contrast it is the ineluctable tendency of later editors, imitators and redactors to introduce retributive justice. Hence, in the end, Jesus the peace-and-joy man on the donkey becomes the mass-slayer on a horse in Revelation. The tendency can be seen, going right back to the arrival of the Deuteronomist as one of the redactors or authors of Genesis in the mid-500s BC. God, in Robert Frost’s poem "A Masque of Reason", says to Job, "You realize now the part you played / To stultify the Deuteronomist / And change the tenor of religious thought". For Crossan as for Frost, the Deuteronomist’s desire to reduce religion to a matter of law-observance, and to introduce the notion of sanction and punishment for the infringement of religious laws, is the enemy of all that the liberating Yahweh brought to the early dawning of Hebrew religious understanding. Crossan’s version of Scripture is certainly attractive, but only up to a point do I find it convincing. The Bible, and life, are more complicated than Crossan would like us to think. If you have a concept of justice and righteousness at all, then a part of that concept must include comeuppance for the wrongdoer. This is not because the Bible – or any other ethical code – is dreamed up by punishment freaks. It is because if there is no sanction, then evil is in effect allowed. If you maintain a belief in transcendent ethics, then heaven cries out against the infringement of justice, as it does through all the great prophets of Israel. Crossan’s reading of Romans is in this respect especially problematic. One of the core ideas of the epistle is that of baptism into death. The followers of Jesus had died to the basic values of Rome’s empire and been reborn to those of God’s sanction – retributive, if you will – and not just "distributive". The atoning death of Christ was necessary for grace to flow. This idea runs through everything Paul wrote and was surely one of the critical ingredients in Christianity from its inception. In an opening chapter, Crossan describes his disgust at a film version of C. S. Lewis’s The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. He contrasts Aslan’s words to Peter, the eldest of the children involved in the Battle against the White Witch of Narnia, with the words of Christ in Gethsemane. "Never forget to wipe your sword," says Aslan, who clearly approves of the children having taken part in what Crossan calls "the divine violence of apocalyptic cleansing". Contrast this with the Jesus of Matthew’s Gospel telling the disciples at the time of his arrest, "all who take the sword will perish by the sword" (Matthew 26:52). Tolstoy, a Jewish expert on Jesus such as Geza Vermes, and many – perhaps most – Church of England bishops today, would certainly accept Crossan’s belief in a pacifist Jesus who preferred to die a martyr’s death at the hands of Pilate rather than make himself the leader of violent revolution. It would be blindness to deny that there is this strain in the New Testament, and perhaps at its core. Perhaps. And yet there are many moment’s as I read Crossan’s book when it struck me that a more accurate subtitle would be "How to read the Bible and still be good American liberal". I tried to imagine Crossan’s project in the hands of Dante Alighieri. The Dantean perception that hell itself it the creation of divine love allowed of a paradoxical but necessary truth. Crossan’s Jesus, who is simply a martyr for distributive justice, cannot save me from my sins. The theme of soteriology does not enter into Crossan’s book, but it is surely one of the key elements of the seven authentic epistles of Paul. Indeed, it forms the very essence of what Crossan rightly calls "his last will and testament, a magnificent summary of… what he was about, and how his Christian Judaism envisaged the destiny of the world". But the only major theme of Romans that Crossan picks up on is dying in order to live. You might think that he would be knocked off his perch by a reading of Romans 13, in which Paul enjoined the Romans to be subject to the governing authorities. But, says Crossan, this section has been "quotes out of context across two thousand years". Paul’s point was not to make the early Christians into worshippers of the state, but – as Romans 12:14 – to "bless those who persecute you". Paul is not afraid that Christians will be killed, but that they will kill. His concern is not that Rome will use violence against Christians, but that Christians will use counter-violence against Rome. "Non-violent reaction to evil from Jesus through Paul is the most basic denial of Rome’s core value of peace through violent victory." That is a point very well made. It does, however, depend on a certain confidence about what the historical Jesus actually taught. The historical Jesus is a notoriously elusive figure. John Dominic Crossan has been one of the most distinguished New Testament scholars of the past few decades. He and Robert Funk founded the Jesus Seminar in the United States, in which 150 or so scholars were quizzed about their confidence in the authenticity of the sayings attributed to Jesus. They voted with coloured beads. A red bead meant you were certain Jesus has said it. Pink meant it was like an authentic Jesus-saying, even if not actually attributable. Grey beads meant that you thought the saying inauthentic but the sort of...

ISBN: 9780281074204

Dimensions: unknown

Weight: 363g

256 pages