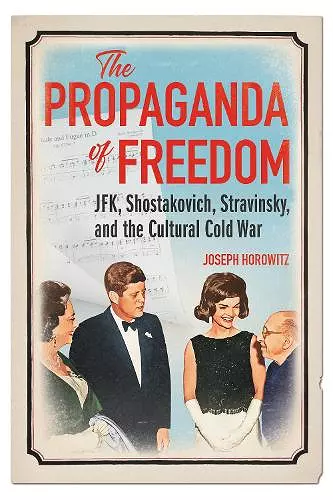

The Propaganda of Freedom

JFK, Shostakovich, Stravinsky, and the Cultural Cold War

Format:Hardback

Publisher:University of Illinois Press

Published:26th Sep '23

Should be back in stock very soon

The perils of equating notions of freedom with artistic vitality

Eloquently extolled by President John F. Kennedy, the idea that only artists in free societies can produce great art became a bedrock assumption of the Cold War. That this conviction defied centuries of historical evidence--to say nothing of achievements within the Soviet Union--failed to impact impregnable cultural Cold War doctrine.

Joseph Horowitz writes: “That so many fine minds could have cheapened freedom by over-praising it, turning it into a reductionist propaganda mantra, is one measure of the intellectual cost of the Cold War.” He shows how the efforts of the CIA-funded Congress for Cultural Freedom were distorted by an anti-totalitarian “psychology of exile” traceable to its secretary general, the displaced Russian aristocrat/composer Nicolas Nabokov, and to Nabokov’s hero Igor Stravinsky.

In counterpoint, Horowitz investigates personal, social, and political factors that actually shape the creative act. He here focuses on Stravinsky, who in Los Angeles experienced a “freedom not to matter,” and Dmitri Shostakovich, who was both victim and beneficiary of Soviet cultural policies. He also takes a fresh look at cultural exchange and explores paradoxical similarities and differences framing the popularization of classical music in the Soviet Union and the United States. In closing, he assesses the Kennedy administration’s arts advocacy initiatives and their pertinence to today’s fraught American national identity.

Challenging long-entrenched myths, The Propaganda of Freedom newly explores the tangled relationship between the ideology of freedom and ideals of cultural achievement.

“The Propaganda of Freedom makes a significant contribution to our understanding of the Cold War. The thesis that an ideology of ‘freedom’ made it impossible for leading American intellectuals to recognize the cultural achievements of Soviet artists during the Cold War is compelling and convincing--even for readers unversed in the cultural or musical history of the twentieth century. Moreover, it exposes one of the weaknesses of an omnipresent American world view: the fallible notion that, by virtue of its devotion to individual liberty, the United States surpasses the rest of the world in its ability to nurture artistic, scientific, and cultural achievement. In fact, all too often American foreign policy is based on the false premise that promoting ‘individual freedom’ must remain at the heart of the nation’s efforts to exert influence abroad.

“The book raises important questions not only about the efficacy of US foreign policy, but also about the relationship between culture and democracy, even about the nature of democracy itself --questions extremely pertinent in a world where populist political movements have called into question democratic norms that once seemed unassailable.

“Above all, it is the author’s extrapolation of a ‘fetishization of freedom’ that makes this work so vital. Horowitz writes: ‘That so many fine minds could have cheapened freedom by over-praising it, turning it into a reductionist propaganda mantra, is one measure of the intellectual cost of the Cold War.’ I would argue that these same reductionist tendencies have played a significant part in the rise of volatile populist movements, as well as in the construction of the so-called war on terror that followed the 9-11 attacks. In this sense, the book serves as a warning that the American tendency towards political and cultural unilateralism is not only naïve, but dangerous.”--David Woolner, Resident Historian, the Roosevelt Institute; author of The Last One Hundred Days: FDR at War and at Peace

“The Propaganda of Freedom is an impressive achievement, a wholly absorbing read, a valid indictment of Nicolas Nabokov and the whole Congress of Cultural Freedom project as supremely misconceived and clumsily executed--something of a mirror image, in fact, of postwar Stalinist Russia itself. In that sense they deserved each other. And there can be no doubt that the approach both countries came to embrace by the late 1950s, enshrined in the 1958 cultural diplomacy agreement, changed many more minds and attitudes over the decades that followed.”--John Beyrle, former United States Ambassador to Russia (2008-2012)

“Readers of Joseph Horowitz’s seminal Understanding Toscanini and Wagner Nights will know what to expect from The Propaganda of Freedom: a brilliant, combative work where the intensity of historical research is matched by the force of analysis. He has spotted what he calls an ‘imposed propaganda of freedom’ in John F. Kennedy’s arts advocacy--an analysis that raises important questions for historians of the Kennedy Administration and the Cold War. Not the least of these is the relationship between the artist (embodied here by Shostakovich and Stravinsky) and the state in Cold War society. As one of the leading cultural historians and public intellectuals of the last four decades, whose world-class research and writing have had such a profound impact on the study of twentieth century American culture, Mr. Horowitz has written another exceptional revisionist work that completely upends our understanding of the cultural Cold War.”--Richard Aldous, author of Schlesinger: The Imperial Historian and Reagan and Thatcher: The Difficult Relationship

“The Propaganda of Freedom, Joseph Horowitz’s fascinating, compact study of Cold War cultural relations, is a timely reminder that ideology not only informs propaganda--whether true or false--but also the key concept of ‘freedom.’ As culture became an exchangeable commodity between the opposing powers of the Soviet Union and the United States (and its Western allies), it became open to manipulation by both sides. Horowitz closely examines the role of the Soviet propaganda machine and the American Congress for Cultural Freedom (funded largely by the CIA) and the key figure of Nicolas Nabokov. He presents fresh perspectives on old arguments and exposes as dubious the idea that culture only exists where there is freedom. The concept was aired in 1949 by opponents of the Cultural and Scientific Conference for World Peace in New York, and later taken up with eloquence by President Kennedy, admittedly not a man of any cultural depth. Horowitz reminds us of the danger of such fallacious arguments, and of the many facetted sides of Soviet art. The purportedly opposing figures of Shostakovich and Stravinsky, seen to represent Soviet and American societies, could both create masterpieces despite different stylistic choices; in the former’s case notwithstanding ideological control and repression, and in the latter’s as an expression of the exile’s hermetic oasis where politics didn’t intrude. In all this, one wonders how Nicolas Nabokov succeeded in selling a festival of avant-garde music in Paris to the CIA--as an act of propaganda or of ‘lavishly bankrolled impetuous opportunity?’”--Elizabeth Wilson, author of Shostakovich: A Life Remembered

“The Propaganda of Freedom newly explores the cultural Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union. It discovers vital connections that previously were wholly hidden from view. An exceptionally timely and consequential study that dramatically changes our understanding of a fascinating chapter in twentieth century cultural history.”--Vladimir Feltsman

"“Horowitz’s historical research is far-reaching and detailed.”" --BBC Music Magazine

ISBN: 9780252045271

Dimensions: 229mm x 152mm x 38mm

Weight: 540g

248 pages